Panacea Journal of Medical Sciences

Panacea Journal of Medical Sciences (PJMS) open access, peer-reviewed triannually journal publishing since 2011 and is published under auspices of the “NKP Salve Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre”. With the aim of faster and better dissemination of knowledge, we will be publishing the article ‘Ahead of Print’ immediately on acceptance. In addition, the journal would allow free access (Open Access) to its contents, which is likely to attract more readers and citations to articles published in PJMS.Manuscripts must be prepared in accordance with “Uniform requiremen...

Role of glypican-3 and heppar-1 in categorization of hepatic space occupying lesions in imaging guided fine needle aspiration cytology

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes 80% of all primary liver cancers. [1] It is the fifth most common cancer in the world and the fourth most common cause of cancer related death globally. [2] HCC constitutes a heterogeneous group of neoplasms with different morphological characteristics, biological and clinical outcomes. Also, liver is the second most common site for metastasis (40-50%) of different primary malignancies. Commonly metastatic deposit in liver originates from the colon, rectum, pancreas, stomach. Majority of liver metastases present as multiple tumour nodules.[3] Glypican-3(GPC-3) promotes cell proliferation by up regulating β-catenin signalling pathway.[4] It is specifically over-expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[5] So, this gene could be a novel therapeutic target for HCC.[6] HepPar-1 is believed to be associated with the membrane of hepatocytic mitochondria. Hep-Par-1 is absent in the mitochondria of other tissues.[7]

The current study aims to assess Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) technique on fifty specimens of suspected hepatic space occupying lesions (SOL) in cell block preparations of Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) material in a tertiary hospital in West Bengal.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India over a span of one year. Ultrasound guided FNAC was performed on fifty patients presenting with hepatic SOL. We followed the standard procedure to make cell block, Leishman and Giemsa stain, Hematoxylin and Eosin stain and Immunohoistochemistry. Suspected hepatic SOLs with age more than 12 years were included in the present study and infective and non-neoplastic lesions of the liver; patients with abnormal coagulation profile and unwilling patients were excluded. The present study was a prospective, observational and interventional study using parameters like patient’s signs, symptoms, radiological investigations along with FNAC findings, Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining of cell block preparations and Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 expression by IHC protocol.

HepPar-1 scoring method: [8]

|

Intensity Score |

Staining Characteristic |

|

0 |

No staining |

|

1 |

Focally weak staining |

|

2 |

Focally strong staining |

|

3 |

Diffuse strong staining |

Glypican-3 Scoring Method: [8]

Strong staining (3+) was clearly visible using 4x objective lens.

Moderate staining (2+) required 10x or 20x objective lens for clear observation.

Weak staining (1+) required40x objective lens.

|

Clinical score |

Staining Characteristic |

|

0 |

Negative membranous and positive cytoplasmic staining in < 10% of tumour cells. |

|

1 |

Positive membranous staining in <10% of tumour cells and /or positive cytoplasmic staining in > 10 % of tumour cells. |

|

2 |

Weak or moderate membranous staining in >10% of tumour cells with or without positive cytoplasmic staining in >10% of tumour cells. |

|

3 |

Strong membranous staining in >10% of tumour cells or strong cytoplasmic staining >50% of tumour cells. |

Statistical Analysis: We analysed the data by SSPS (version 27.0; SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 5. Data had been summarized as mean and standard deviation for numerical variables and count and percentage for categorical variables. The P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethics

The present study was conducted in Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India after obtaining institutional ethical clearance (NMC/10017, dated 08.01.2019).

Results

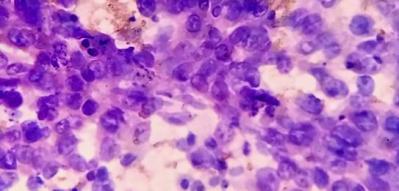

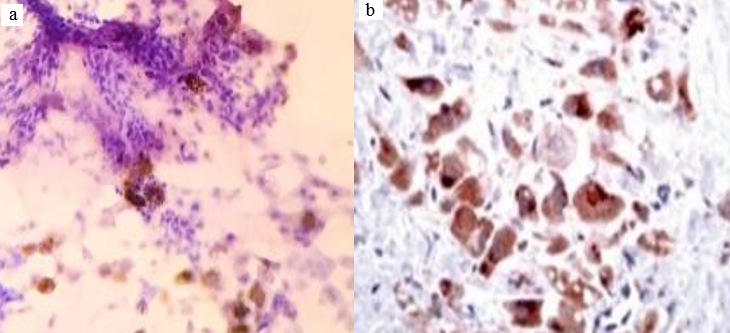

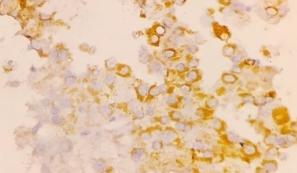

In present study, majority of the patients, i.e. 22(44.0%) were 41-50 years old with male preponderance, i.e. 58%.20 cases (40%) had history of alcohol intake, 8 cases (16%) had history of cirrhosis. 24 cases (48%) presented with abdominal lumps, among which 4 (8%) cases were primary HCC and 20 cases (40%) were of different metastatic carcinomas.39 cases (78%) were associated with weight loss; among them 9 cases (18%) were primary HCC and 30 cases (60%) were metastatic carcinomas. On radiological interpretation, 28 cases(56%) showed multiple lesions and 22(44%) cases showed solitary lesions. Among the multiple lesions,02 cases (4%) were primary HCC lesions and 26 (52%) lesions were metastatic lesions. Among the solitary lesions, 11cases (22%) were primary and 11 (22%) cases were metastatic. On cytology, 50 cases were divided into liver primary and metastatic lesions. Cytologically we found 9 cases but in cell block 11 cases (22%) of HCC were found. Grade wise, Grade I - 6 cases (55%), Grade II - 4 cases (36%) and Grade III – 1 case (9%) ([Figure 1], [Figure 2]). Statistically significant correlations were noted among the radiological lesions, Glypican-3 staining and HepPar-1 staining score i.e. (p=0.04) and (p=0.0166) respectively [[Table 3], [Table 4]]. Regarding metastatic lesions in cell block, we found 7 cases (14%) of lung carcinoma, 6 cases (12%) of breast carcinoma, 6 cases (12%) of gall bladder carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma of unknown origin 5 cases (10%), ovarian adenocarcinoma metastasis 4 cases (8%), pancreatic adenocarcinoma 3 cases (6%), cholangiocarcinoma 2 cases (4%), gastric adenocarcinoma 2 cases (4%) and colonic adenocarcinoma 1 case (2%). Apart from this, inconclusive result came in one case in cell block (2%) ([Table 5]). All metastatic lesions were negative for these immunomarkers. 44 cases (88%) were diagnosed cytologically and confirmed by cell block evaluation. Rest of 6(12%) cases could not be interpreted properly by cytology. Among 6 cases (12%), three cases interpreted cytologically as metastatic carcinoma turned out to be two primary HCC and one case of angiomyolipoma. Three inconclusive cases of cytological interpretations were later diagnosed as small cell carcinoma of lung and gall bladder carcinoma. One case remained doubtful even on cellblock evaluation due to inadequate material.45 (90%) cases were negative for Glypican-3, 4 (8%) were moderately (2+) and 1 case(2%) was strongly positive (3+)([Figure 3]a,b).40 (80%) cases were negative for HepPar-1, 5 (10%) were focally weak stained (1+) and 5 (10%) were focally strong(2+) ([Figure 4]). We found positive association amongst HCC grade, Glypican-3 staining score and HepPar-1 staining score i.e., (p=0.0053) and (p=0.0093)([Table 6], [Table 7]) respectively. Among 8 cases of cirrhosis, only 5 cases (62.5%) were positive of Hep par 1, P value was significant 0.001%.10 (20%) cases of primary HCC were HepPar-1 positive, out of which 5cases (10%) in each staining intensity focally weak (1+) and focally strong (2+). Correlation between two parameters were statistically significant (p=0.0004). In Grade I HCC, HepPar-1 andGlypican-3 expression was seen in 4 cases (66.7%) and 1(16.67%) case respectively. In Grade II primary HCC, HepPar-1 and Glypican-3 expression was seen in 4 cases (100%) and 3 cases (75.0%) respectively. In Grade III primary HCC, HepPar-1 expression was not seen, while Glypican-3 expression was seen in 1 case (100%) of HCC. Maximum number of HCC was grade I (6). Among them, 4 samples (66.7%) were positive for HepPar-1 (score2+) and only one sample which was a fibrolamellar variant of primary HCC was seen positive with Glypican-3 (score2+). Among 4 Grade II HCCs, 4 cases (100%) were positive for HepPar-1(score 2+) and 3 cases (75%) were positive for Glypican-3 (score 2+). One case (100.0%) of Grade III HCC showed positivity with Glypican-3(score 3+). Glypican-3 staining expression on neoplastic hepatic SOL (both primary and metastatic) yielded a sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 41.6%, 100% and 86% respectively. HepPar-1 staining expression on neoplastic hepatic SOL (both primary and metastatic) yielded a sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 75%, 97.4% and 92% respectively. Together, Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 staining expression on neoplastic hepatic SOL (both primary and metastatic) yielded a sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 83.3%, 97.4% and 94% respectively.

|

Radiological Interpretation |

Glypican-3 Staining Score |

Total |

||

|

0 |

2 |

3 |

||

|

Multiple SOLs |

27 (96.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3.6%) |

28 (100%) |

|

Solitary SOL |

18 (81.8%) |

4 (18.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

22 (100%) |

|

Total |

45 (90.0%) |

4 (8.0%) |

1 (2.0%) |

50 (100%) |

|

Radiological Interpretation |

HepPar-1 Staining Score |

Total |

||

|

0 |

2 |

3 |

||

|

Multiple SOLs |

26 (92.9%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (7.1%) |

28 (100%) |

|

Solitary SOL |

14 (63.6%) |

5 (22.7%) |

3 (13.6%) |

22 (100%) |

|

Total |

40 (80.0%) |

5 (10.0%) |

5 (10.0%) |

50 (100%) |

|

Cases |

Cytology |

Cell Block With IHC |

Total cases in cell block |

|

Primaryhepatic lesions |

HCC(09) |

HCC(11) |

|

|

|

Hepatic Adenoma(1) |

Hepatic Adenoma (1) |

13 |

|

|

|

Angiomyolipoma (1) |

|

|

Metastatic carcinomas |

|||

|

Breastcarcinoma |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

Lungcarcinoma |

Non Small Cell Ca -4 |

Non Small Cell Ca-5 |

7 |

|

|

Small Cell Ca-2 |

Small Cell Ca – 2 |

|

|

Gallbladder carcinoma |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

Cholangiocarcinoma |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Gastric adenocarcinoma |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Pancreaticadenocarcinoma |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

Ovarianadenocarcinoma |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

Metastasis of unknown origin |

7 |

5 |

5 |

|

Colonicadenocarcinoma |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Inconclusive |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

50 |

50 |

50 |

|

Grade of HCC |

Glypican-3 Staining Score |

Total |

||

|

0 |

2 |

3 |

||

|

Grade I |

5 (83.3%) |

1 (16.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (100%) |

|

Grade II |

1 (25.0%) |

3 (75.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (100%) |

|

Grade III |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (100%) |

1 (100%) |

|

Total |

6 (54.5%) |

4 (36.4%) |

1 (9.1%) |

11 (100%) |

|

Grade of HCC |

HepPar-1 Staining Score |

Total |

||

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

||

|

Grade I |

2 (33.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (66.7%) |

6 (100%) |

|

Grade II |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (100.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (100%) |

|

Grade III |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (100%) |

|

Total |

3 (27.3%) |

4 (36.4%) |

4 (36.4%) |

11 (100%) |

Discussion

The clinical history and routine investigations of 50 cases were recorded. Cytological evaluations with IHC staining was done and correlated with various available clinicopathological parameters. The result obtained was compared with other studies done by various workers. The age ranged from 20-80 years with a mean age of 54.3 ±10.78 years. Most of the lesions were found between the 41-50 years with 22 patients (44%). We got two benign tumours (hepatic adenoma and hepatic angiomyolipoma). The present study was similar to El-Serag HB et al[9] and Bruno S et al. [10] There was male preponderance (58%) with the ratio of Male: Female of 1.4: 1, similar to Shafizadeh N et al[11] and Lai CL et al. [12] We got 20alcoholic patients (40%) among them 5 patients (25%) developed HCC. So, there was a positive correlation between alcohol intake and hepatocellular carcinoma. The present study was in concordance with the findings of El.Serag HB et al study. [9] Among the risk factors, liver cirrhosis was one of the most common contributors related to HCC. We found 8 cases (16%), among which 6 patients of primary hepatocellular carcinoma were directly related to cirrhosis with a contribution of about 12 % and 2 cases (4%) were diagnosed as metastases in liver from pancreas, similar to the studies done by Mazzella Getal[13] and RosarioF. Velazquez et al. [14] Weight loss was noticed in 39 cases (78%), among them 9 cases were HCC and 30 cases were metastatic; 26 cases (52%) presented with abdominal lumps among which 4 cases were HCC and 22 cases were metastatic carcinomas, a finding in concordance with Mitsuteru N et al.[15] On radiological interpretation, 28 cases(56%) were multiple lesions and 22(44%) cases were solitary. Among the solitary lesions, 11cases (22%) were primary and 11(22%) cases were metastatic in nature. Among the multiple lesions, 2 cases (4%) were primary HCC and 26 cases (52%) were metastatic in nature. These findings were consistent with the Thahirabi KA et al [16] and Noguchi Set al. [17] Cytologically, we detected 10 primary hepatic lesions [9(18%) HCC and 1(2%) hepatic adenoma]. In cell block, we got 13 cases of primary hepatic lesions (11 HCC, 1 hepatic adenoma and 1 angiomyolipoma).Among metastatic lesions, lung carcinoma metastasis 7 cases (cytology 6 cases) (14%), 6 cases (12%) of breast carcinoma, 6 cases (12%) of gall bladder carcinoma (cytology 5 cases), metastatic carcinoma of unknown origin 5 cases (10%)(cytology 7 cases), ovarian adenocarcinoma metastasis 4 cases (8%), pancreatic adenocarcinoma 3 cases (6 %)(cytology 4 cases),cholangiocarcinoma 2 cases (4%), gastric carcinoma 2 cases (4%) and colonic adenocarcinoma one case (2%). Apart from this, inconclusive result came in one case only (2%) (cytologically three inconclusive cases i.e. 6%). Present study showed cytological evaluation had 90.9% sensitivity with 94.9% specificity and 94.0% accuracy which was statistically significant (p=0.012) and in concordance with Azad AK et al[18] and Yamauchi N et al. [19] The study proved that Ultrasound guided FNAC was a very simple, rapid, inexpensive, minimally invasive and most accurate diagnostic method for cytological diagnosis of HCC. This study also proved that cell block is 100% sensitive and specific to detect and differentiate liver primaries from metastatic liver lesions. We found that Glypican-3 was mostly positive in HCC, while metastatic lesions were negative for it. Staining intensity was more in poorly differentiated carcinomas than in well and moderately differentiated carcinomas. The findings were consistent with Lai CL et al [12] and Alessandro L et al. [20] Immunohistochemically, 40(80%) were negative for HepPar-1. Among positive cases, 5 (10%) were focally weak stained (1+) and 5 (10%) focally strong stained (2+). The positive cases were mostly liver primaries, concordant with the Leong AS et al [21] and Coston WM et al. [22] We got 11cases (22%) of HCC, out of which Grade I, Grade II and Grade III HCC cases were 6 (55%), 4 (36%) and 1 (9%) respectively, which were consistent with Chalasani N et al[23] and Lai CL et al [12] studies. Statistically significant correlation was found between radiological lesions and Glypican-3 staining score(p=0.04), concordant with the findings of Ibrahim TR et al. [24] In this study most of the primary HCCs were HepPar 1 positive and metastatic tumours were negative. Most of the HCCs were solitary whereas metastatic carcinomas were multiple on ultrasonography similar to Leong et al. [21] In cell block, among the 44 confirmed cases (88%) and 6 unconfirmed cases (12%) of liver malignancies, Glypican-3 only showed positivity for liver primaries. 5 liver FNAC samples were stained positive for Glypican-3, among which 4 cases (8%) were moderately differentiated (Grade II) and one case (2%) was poorly differentiated (Grade III) primary HCC. However, correlation was not statistically significant (p=0.87), similar to the studies by Shirakawa H et al[25] and Kakar S et al [26]. Most of the primary HCC was solitary lesions; whereas metastatic carcinomas were multiple on ultrasonography. The present study finding was concordant with the Thahirabi KA et al[16] and Coston WM et al. [22] Among 11 cases of HCC, 10 cases (91%) were HepPar-1 positive out of which among 5 cases, staining intensity was focally weak (1+) and among rest of the 5 cases, focally strong (2+). Focally strong staining was Grade I primary HCC and focally weak staining were Grade II primary HCC. One hepatic adenoma (2%) and one colonic adenocarcinoma (2%) were also positive for HepPar-1. Correlation between two parameters was statistically significant (p=0.005), consistent with Wennerberg AE et al[27] and Momin TS et al. [28] In this study 3 cases of primary hepatocellular carcinomas (75%) were grade II (moderately differentiated) and one case of primary Hepatocellular carcinoma (25%) which was a fibrolamellar variant of primary HCC was grade I (well differentiated). These 4 cases were stained positive for Glypican 3 (Score 2+). Also, there was a grade III (poorly differentiated) carcinoma which was stained positive with Glypican3 (Score 3+). Glypican 3 expression was more in moderately and poorly differentiated primary HCC than well differentiated HCC. Association between Glypican 3 and grading of primary HCC was statistically significant (p=0.0053) and concordant with the findings of Coston WM et al. [22] In present study, both Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 were positive in Grade II primary HCC (4 out of 4 cases showed positivity), while Grade I primary HCC were invariably positive for HepPar-1 and negative for Glypican-3 with an exception of fibrolamellar variant of primary HCC. Grade III primary HCC was positive only for Glypican-3. The sensitivity and specificity of Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 were 41.6%, 100% and 75.0, 97.4 % respectively. Their combined sensitivity and specificity were 83.3% and 97.4% respectively with an accuracy of 94.0%.

Conclusion

Guided FNAC is a minimally invasive technique. It helps to detect and categorize neoplastic hepatic lesions in conjunction with cell blocks and IHC markers. Combined use of Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 markers differentiate between HCC and metastatic hepatic lesions, clearly. Early accurate diagnosis enables the clinician for proper management, so increasing the longevity of patients. Also, Glypican-3 can be used as a novel therapeutic agent for targeted therapy of primary liver cancer.

Source of Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- RX Zhu, WK Seto, CL Lai, MF Yuen. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. Gut Liver 2016. [Google Scholar]

- . World Health Organization. Prevalence of hepatocellular cancer, Global Health Observatory Data. WHO Geneva, Switzerland 2018. [Google Scholar]

- . NIH: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- M Yao, LH Pan, DF Yao. Glypican-3 as a specific biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015. [Google Scholar]

- B Yan, JJ Wei, YM Qian, XL Zhao, WW Zhang, AM Xu. Expression and clinicopathologic significance of glypican 3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2011. [Google Scholar]

- A Flores, JA Marrero. Emerging Trends in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Focus on Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Z Fan, M Van De Rijn, K Montgomery, RV Rouse. Hep par 1 antibody stain for the differential diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: 676 tumours tested using tissue microarrays and conventional tissue sections. Mod Pathol 2003. [Google Scholar]

- KD Miller, JD Bancroft, M Gamble. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. Immunohistochemical techniques 2002. [Google Scholar]

- HB El-Serag. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002. [Google Scholar]

- S Bruno, E Silini, A Crosignani, F Borzio, G Leandro, F Bono. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology 1997. [Google Scholar]

- N Shafizadeh, L D Ferrell, S Kakar. Utility and limitations of glypican-3 expression for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma at both ends of the differentiation spectrum. Mod Pathol 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CL Lai, KC Lam, KP Wong, PC Wu, D Todd. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma: review of 211 patients in Hong Kong. Cancer 1981. [Google Scholar]

- G Mazzella, E Accogli, S Sottili, D Festi, M Orsini, A Salzetta. Alpha interferon treatment may prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1996. [Google Scholar]

- RF Velazquez, M Rodriguez, CA Navascues, A Linares, R Pérez, NG Sotorríos. . Hepatology 2003. [Google Scholar]

- M Natsuizaka, T Omura, T Akaike, Y Kuwata, K Yamazaki. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma with extra hepatic metastases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005. [Google Scholar]

- KA Thahirabi, E Daniel, MN Brahmadathan, KP Raini. Usefulness of Ultrasound in Characterization of Focal Hepatic Lesions. J Med Sci Clin Res 2017. [Google Scholar]

- S Noguchi, R Yamamoto, M Tatsuta, H Kasugai, S Okuda, A Wada. Cell features and patterns in fine-needle aspirates of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 1986. [Google Scholar]

- AK Azad, H Masud, PK Roy, A Raihan, MT Rahman, M Hasan. The Role of Ultrasound Aided Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) in the Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Bangladesh J Med 2001. [Google Scholar]

- N Yamauchi, A Watanabe, M Hishinuma, K Ohashi, Y Midorikawa, Y Morishita. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2005. [Google Scholar]

- A Lugli, L Tornillo, M Mirlacher, M Bundi, G Sauter, LM Terracciano. Hepatocyte paraffin 1 expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues: tissue microarray analysis on 3,940 tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol 2004. [Google Scholar]

- AS Leong, RT Sormunen, WM Tsui, CT Liew. Hep Par 1 and selected antibodies in the immunohistological distinction of hepatocellular carcinoma from cholangiocarcinoma, combined tumours and metastatic carcinoma. Histopathology 1998. [Google Scholar]

- WM Coston, S Loera, SK Lau, S Ishizawa, Z Jiang, CL Wu. Distinction of hepatocellular carcinoma from benign hepatic mimickers using Glypican-3 and CD34 immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol 2008. [Google Scholar]

- N Chalasani, JC Horlander, A Said, H Hoen, KK Kopecky, SM Stockberger Jr. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999. [Google Scholar]

- TR Ibrahim, SM Abdel-Raouf. Immunohistochemical Study of Glypican-3 and HepPar-1 in Differentiating Hepatocellular Carcinoma from Metastatic Carcinomas in FNA of the Liver. Pathol Oncol Res 2015. [Google Scholar]

- H Shirakawa, T Kuronuma, Y Nishimura, T Hasebe, M Nakano, N Gotohda. Glypican-3 is a useful diagnostic marker for a component of hepatocellular carcinoma in human liver cancer. Int J Oncol 2009. [Google Scholar]

- S Kakar, T Muir, LM Murphy, RV Lloyd, LJ Burgart. Immunoreactivity of Hep Par 1 in hepatic and extrahepatic tumors and its correlation with albumin in situ hybridization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2003. [Google Scholar]

- AE Wennerberg, MA Nalesnik, WB Coleman. Hepatocyte paraffin 1: a monoclonal antibody that reacts with hepatocytes and can be used for differential diagnosis of hepatic tumors. Am J Pathol 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MT Siddiqui, MH Saboorian, ST Gokaslan, R Ashfaq. Diagnostic utility of the HepPar1 antibody to differentiate hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration samples. Cancer Cytopathology 2002. [Google Scholar]

Article Metrics

- Visibility 6 Views

- Downloads 3 Views

- DOI 10.18231/j.pjms.2024.139

-

CrossMark

- Citation

- Received Date April 21, 2023

- Accepted Date December 07, 2023

- Publication Date December 21, 2024